59-7. 41-0. 63-7. 55-7. 63-9. 55-7. 54-17. No, these are not winning lottery numbers or three unconventionally written phone numbers. These are just a few of the final scores of football games between nationally recognized historically black universities and predominantly white institutions this fall.

Despite the embarrassment of losing by such a wide margin, the results were not unexpected by these schools. In fact, they may have been welcomed. For the better part of the last three decades, PWIs have scheduled HBCUs early in both their football and basketball seasons for what many consider to be “warm-up” games. According to USA Today, more often than not in exchange for the nearly guaranteed demoralizing loss, HBCUs receive a payment ranging anywhere from tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars from their opponent.

One of and presumably the key reason PWIs are comfortable scheduling HBCUs for these “warm-up” games is the fact that the talent disparity between the two has been no secret for decades now. Players at PWIs are often bigger, stronger, faster and more coveted out of high school than those you find at HBCUs, especially in football.

“I covered the Bayou Classic (annual football game between HBCUs Southern and Grambling State) this year and since then I’ve been telling everyone around the office how the difference in size is perceptible,” John Miller, senior editor at ESPN’s “The Undefeated” recounted when asked about the disparity between HBCUs and PWIs. “For example, linemen at Power Five schools are probably 6’3 or 6’4 and 300 pounds on average, while HBCUs will have one or two players like that total.”

While size alone may not be the only factor that determines how well a player performs on the field or court, it plays a major role without a doubt. Size matters in sports, and the bigger, faster players always seem to choose PWIs. Why is that the case? The difference in money contributes to a variety of reasons these athletes tend to prefer PWIs over HBCUs.

Marginal TV time

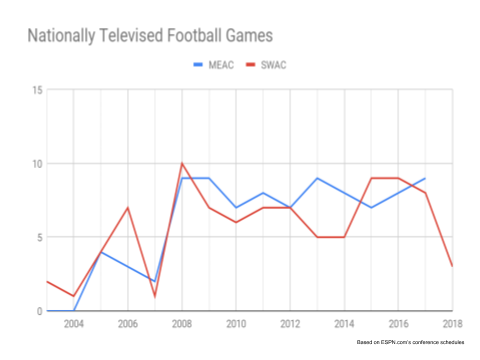

Growing up, HBCUs are not on the radar of many athletes because of the lack of television exposure they receive in comparison to PWIs. Over the course of the 2018 college football season, only nine HBCU games were broadcast on one of the main ESPN/ABC, NBC, CBS or Fox Sports networks, with one of those games being a 45-9 Nebraska victory over Bethune-Cookman University.

“When I was young, I never really seen HBCUs on TV. It was only [Power Five] schools like Michigan State,” says former Florida A&M football player Adam Mattison. “I always wanted to go to a school like that because I felt they gave me the best chance to make it to the NFL.”

As children, seeing an HBCU Saturday mornings on a national network was a rarity for this generation of athletes. Since 2003, when Mattison and other college players would have still been in elementary school, according to ESPN’s conference schedules (which display what network, if any, will broadcast games) HBCUs have only been in nationally televised football games about 12 times per season on average. To put that into perspective, Michigan State’s conference, the Big Ten, had twelve national television slots alone the second week of the 2017 season.

Lopsided Revenue

Exposure is not the only thing PWIs get for dominating the college football airwaves every weekend, either.

“[Power Five conferences] see huge amounts of money from the deals they make with these TV networks,” Miller explained. “We (ESPN) just paid the Big Ten over a billion dollars to cover their games. You factor in Turner and Fox and that’s probably over another billion. That money gets divided amongst the programs and they use it to enhance their facilities and appeal to the best players.”

According to a report by Jon Wilner, former Football Writers Association of America beat writer of the year, in the 2018 fiscal year Power Five programs are projected to see tens of millions of dollars in revenue splits from deals such as the one the Big Ten has with ESPN. Big Ten schools are projected to come out the wealthiest, averaging over $50 million in revenue per team, while ACC schools rank last out of the five conferences with a projected average revenue of $28 million.

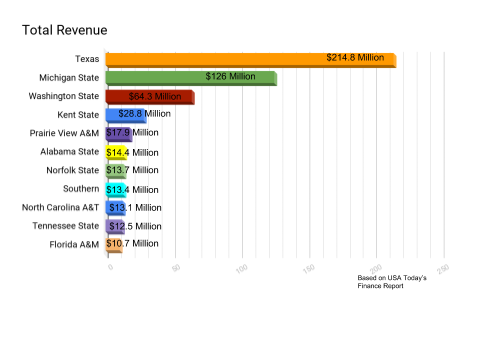

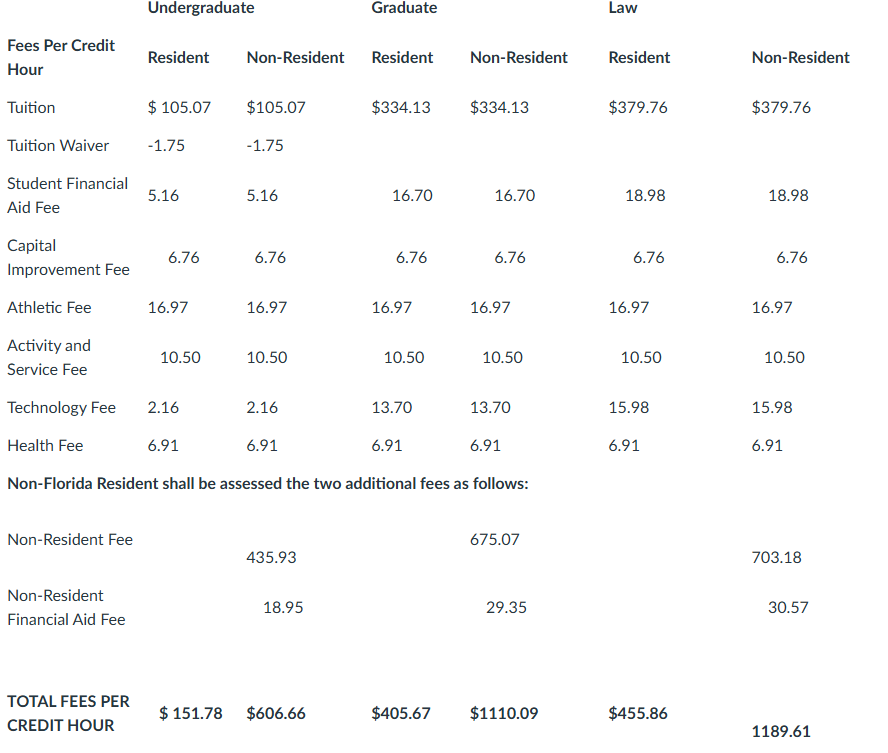

In comparison, in USA Today’s latest NCAA finances report, Prairie View A&M was the highest ranked HBCU with $17.9 million in total revenue. The figures from Wilner’s report only accounts for payment from a Power Five conference to a school, while USA Today’s report takes every revenue stream the schools have into account. Even the Power Five program with the least total revenue, Washington State of the PAC 12, had nearly twice the total revenue of Prairie View A&M and Alabama State, the second highest ranked HBCU, combined.

“As players, we want to play for the best teams that are in college, which are FBS and Power Five schools,” claims Central State defensive end Shemar Moss. “These schools provide the most resources and exposure because of their program history and the money the school gets. As athletes, we like those schools [more than HBCUs] because we feel as if we have a better chance at playing pro football coming from those schools. It’s possible to make it from an HBCU, but the road to the pros may seem a little harder and you are going to have to stand out more.”

As told by Moss, who played for predominantly white Kent State before transferring to the historically black Central State, it is hard for HBCUs to compete with the amount of money PWIs put into their programs.

“When you look at PWIs, even the smaller schools provide their teams with everything they need and then some. Their fields and weight rooms are way better. Off the field, there are more resources and more classes offered. The campus food is better and the uniforms and the amount of gear given to the athletes as well. All these things play a role in determining where you want to play football when you’re coming out of high school, especially for the more highly rated players.”

The fact that Moss transferred from a Division I football program in Kent State to Central State’s Division II program also plays a role in Moss’ perspective when comparing the amenities the teams he has played for could offer their players. Be that as it may, the HBCUs in Division I are outclassed by his former school as well. Kent State, a Group of Five school, ranked 46 spots ahead of Prairie View A&M in USA Today’s report with over $28.8 million in revenue.

So, what can HBCUs do to try to get on even playing ground with PWIs? Miller says they should negotiate more lucrative television deals, while Mattison and Moss both believe the schools should try to get the players more exposure somehow. HBCUs are doing what they can to make both of those things happen.

In 2015, the SWAC and MEAC collaborated with ESPN Events for the inaugural Celebration Bowl, which generated millions of dollars for both conferences. The Celebration Bowl, which pits the champion of the SWAC against the champion of the MEAC, has kicked off ESPN’s college football bowl season for four consecutive seasons now.

In August, the MEAC announced that the conference had entered into a multi-year agreement with ESPN for their football games to be available for streaming on the media giant’s ESPN3 and ESPN+ services, resulting in all but eight MEAC games being available for viewers this fall.

Time will tell if the recent measures taken by HBCUs will be enough to narrow the talent gap in future generations.