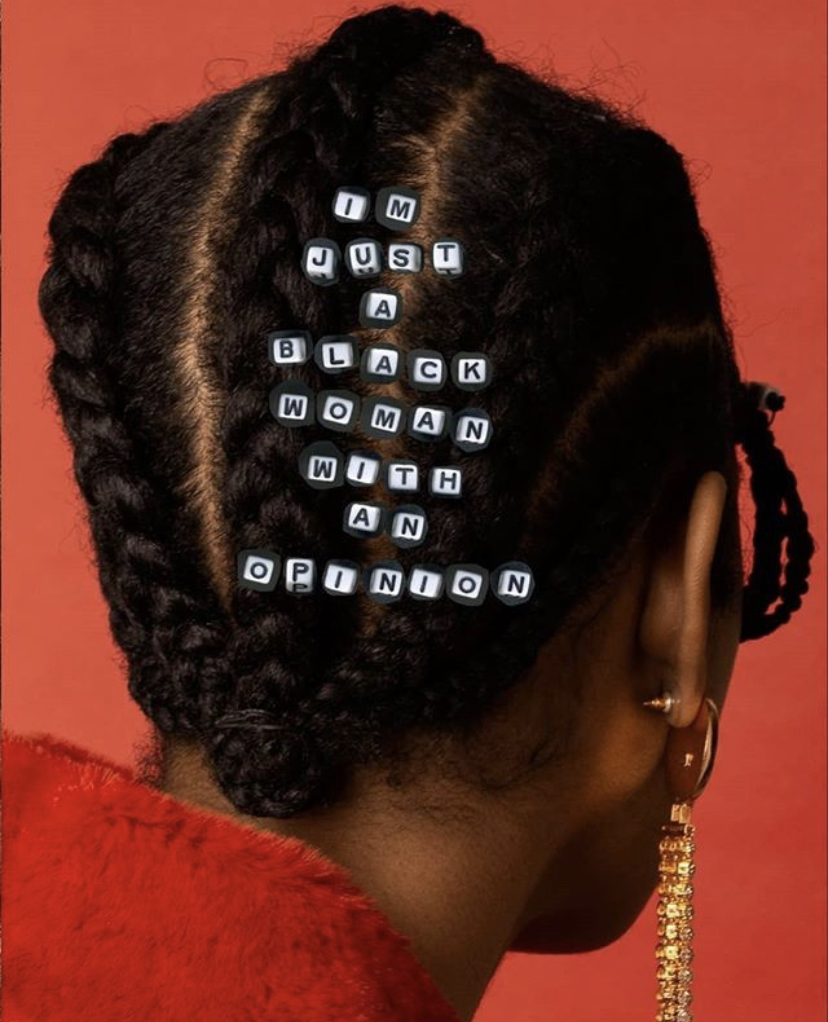

In this op-ed, Florida A&M University freshman and writer Mia Uzzell explains the cultural complexities of black hair in the workplace and how it disrupts the harmony between the image and the identity of African American women.

In the genetic makeup of hair follicles, the recombination of dominant and recessive alleles ultimately results in two hair types: curly or straight. Although rudimentary in genetic composition, its phenotypic expression generates a multitude of subunit hair types varying from looped waves to corkscrew curls.

At first glance, ethnic ties can easily be identified by one’s coiffed strands. Most notably, African women delved into this notion of hair identity by embracing their tribal heritage through the adornment of their crowning glory. Unfortunately, their forced labor, a consequence of the transatlantic slave trade, left the once vibrant celebration of their hair oppressed under the sweltering sun. Rooted in emancipation, African-American women still find themselves seeking to blossom in the liberty of their natural hair amidst the grueling dissection of their image in their workplaces and schools.

Moving On Up

Post emancipation, black women associated the freedom from their field turbans with immediate access into the beauty realm. Under this tropical license to express themselves through their hair, they began to release their coarser textured afros’ from confinement. Gradually traversing away to the North for career opportunities, the cultural pride in their hair was quickly jolted by the reality of America: the stark distinction between the North and the South.

Northern municipalities were centered around corporate, city structures. Such structures were inculcated with Eurocentric mores from its emergence — mores that implanted Caucasian aesthetics as the judge and jury of beauty politics. This abruptly ceased the short-lived connection between African-American women and their roots as assimilation was a smoother route of survival in this new avenue of labor. Black women, eager to enter into the workforce, opted for sleek, cosmopolitan tresses that matched that of their white counterparts. Thus, the precedent of professionalism aligning with these discriminatory standards was set in stone.

In hindsight, women of that time should not be vilified for easing their transition into the career realm, but it is imperative to understand the consequential gravity of this decision through the lens of the ongoing penalization on natural hair in the workplace.

Even while camouflaging, black women still inhabited a disparate career world of lower wages, racially charged hostile work environments, and a callous disregard towards their immense contributions. These facets of their experience, bound to intensify over time, received a catalytic response among the new generation of the 70s and 80s.

Peace, Love, & Discrimination

Draped in braids and donning their teased do’, African American women reached a level of individuality piqued by their inability to fit in. During this self-love journey, white women began to appropriate these hairstyles to attain what they deemed an exotic look.

Plaguing the silver screen with this trend, Bo Derek, a white actress, achieved national notoriety for wearing cornrows in her film debut 10. As white women were heralded for styles without formal backlash in mainstream media, many African American women noted this and rightfully ventured with their hair expression in their places of work. Slighted by the negative tropes attached with their natural hair, if not on a white woman, many found themselves the subject of calculated grooming policies.

Renee Rogers, an African-American woman, styled her hair into cornrows and casually presumed her role as an airport operations agent at American Airlines the following day. Much to her dismay, the employee policies prohibited her from wearing “all-braided hairstyles” at work. She appealed this heinous policy in Rogers v. American Airlines (1981) where she argued a disparate impact claim based on race in which the company, with or without intent, generated an adverse effect on a particular group.

The court rejected this argument of racial discrimination and ruled the hairstyle was merely the product of the “Bo Derek Braids” fad and not “reflective of [the] cultural, historical essence of the Black women in American society” as the plaintiff claimed.

It begs the question of why black women must, once again, confine who they are for a daily average of eight labor hours while the world around them continues to bite their ethnic centered style and flair 24/7.

This ruling in the judicial system was reflective of the ruling of black women in society: the credit for and acknowledgment of black culture is easily disposed of in places dominated by those who capitalize on their experience.

A New Era

The currents of black women washed away by the commercialization of their culture in the 21st century have left the self-identity of African American girls in disarray.

The Kardashian family and social media influencers have niche partitioned sectors of black hair to capitalize off of the shock value, from their purported racial ambiguity, that has morphed them into household names. Whitewashed under this method, bantu knots, cornrows, and the infamous baby hairs have been offensively coined respectively as mini buns, boxer braids, and slicked tendrils.

In the era of social media, black girls experience the dissonance between the glorification of appropriated hairstyles on their timelines and the derision of their hairstyles in their schools.

Mystic Valley Regional Charter School, reflecting the sentiments of other schools with a predominantly white administration, banned two African American students from participating in school sports and prom for flaunting box braids. Located in Malden, Boston, the school released an official statement declaring that the expensive nature of the extensions heightened the “dissimilar socioeconomic backgrounds” between students and shifted the classroom from an educational to a materialistic focus.

Intricate hairstyles, expensive or not, are a part of a universal black girl childhood where countless hours are spent between our mother’s legs getting our hair greased, braided, or hot combed weekly. This claim signals to the community of black youth that their culture causes discomfort in the very spaces they inhabit frequently and that they must condense their ethnic celebration to the confines of their home.

So, what do we instruct our black girls to do as they grow up into women? Should they assimilate to conformist doctrine to avoid these racial microaggressions? Or, can they diverge from a systemic path of indoctrination that will never fully accept them?

These questions may not have an objective answer, but as for now, one thing rings true in the compass of morality. One should never be forced to choose between ethnic expression or societal acceptance. A path should be forged where no one stands in solitude in the fight for inclusivity. Stony may be the road we trod, but the dialogue around hair injustice must begin.

Pillars of our nation, such as the United States Army, are beginning this dialogue and turning to face the rising sun of a new day. A day in which black culture is considered an immutable characteristic, ingrained in our genetics, unable to be changed by the ways of mankind. And most of all, a day where black women can blossom and cultivate the essence of their beauty freely.