On Feb. 26, 2012, Trayvon Martin, like many teenage boys across the nation, huddled around the television to watch the annual NBA All-Star game. Martin, who was visiting his father in a gated Orlando community, walked to a nearby 7-Eleven during halftime to purchase snacks for his younger brother. His trip to the convenience store — a trip that Black teenagers from the inner city to the suburbs are culturally accustomed to — turned fatal. En route back to his father’s residence, the 17-year-old high school junior was fatally shot by George Zimmerman, a neighborhood watch volunteer, on the grounds of suspicion.

The news flooded homes across the nation and Trayvon Martin became a headline primed to be indelibly etched into America’s history. Martin was an unarmed high schooler wearing a black hoodie, wielding only an Arizona Tea and a bag of Skittles. For many, Martin’s death ghastly reflected the country’s teeming rage against injustice. For Generation Z, it was their first palpable memory that unveiled the vile inequities that exist in the proverbial system. As protests akin to the Million Hoodie March erupted nationwide, the generation that was emerging in a digital arena observed the cumbersome beginnings of bearing witness to, parsing and processing the world around them through social media.

As elementary, middle and high school students, they turned to their virtual enclaves to mobilize their own forms of protests. With the revolutionary power invested in them by Tinker v. Des Moines, students arrived in their classrooms in black hoodies, clutching Arizona Tea and Skittles to protest the unjust murder of a Black boy. Unbeknownst to them, Trayvon Martin’s untimely death signified the onset of their fight for justice.

Eight years later, Generation Z is still protesting the death of unarmed Black people.

To be Black in America is to be endangered when jogging, selling CDs outside of the gas station, sleeping in your car, sitting in Starbucks, operating a lemonade stand, barbecuing at a park, working out at the gym, sitting at home and returning from the convenience store. To be Black in America is to peer through timelines and watch the brandishing of privilege in criminally inaccurate police calls imbued with racially-biased accusations. To be Black in America is to scrupulously pore over federal, state, and municipal level legislation and still be abused by the greater carceral state. Black Gen Z, by way of digital guerilla journalism, has seen social media sorely lay bare the unsettling world that they experience in unprecedented magnitude.

Many of those whose first account of brutality is traced to Martin’s death are current Black college students who are a part of a burgeoning vanguard to dismantle dilapidated systems. Now, as 18 to 23-year-olds, they have a grim recollection of videos where Black men, women and children endure a brazen abuse of power. From behind their screens, the virtual unfurling of a watershed of brutality has jolted them into reinventing the revolution on their terms and conditions. To be young and Black in America right now is to be living through a racial divide completely uncensored.

Creating a Path of Their Own

By: Mia Uzzell

On May 25, George Floyd, a 46-year-old black man, was killed in police custody in Minneapolis, Minn. after a convenience store employee reported to 911 that Floyd purchased cigarettes with a counterfeit $20 bill.

The nation was at a standstill as it watched Minneapolis in the throes of outrage following Floyd’s death. Ashleigh Hall turned to her bubble of familiarity, her phone, to try to grasp the series of events she watched flash across the news. Galvanized by footage and protests alike, the Florida A&M University student turned to a GroupMe chat — a conversational platform used frequently by college students — with HBCU students to sift through the next steps of mobilizing a protest.

Hall resides in Tallahassee, Fla., a city rife with racial divisions. The state capital is home to massive gentrification, a gaping town and gown divide and modern-day segregation. Only a few days prior to Floyd’s death, the city’s police department was undergoing a spate of criticism for its negligence in the officer-involved shooting of Tony McDade, an unarmed transmasculine person.

To her dismay, Hall wasn’t met with the same immediacy, so she took her frustrations to Twitter in the early hours on Friday, May 29. From behind her screen, Chynna Carney, a FAMU freshman, was also expressing her need to “do something” in the city where racism isn’t solely reminiscent of the past. In a tale of two tweets, two girls who had never crossed paths before were unknowingly about to embark on a journey for justice together.

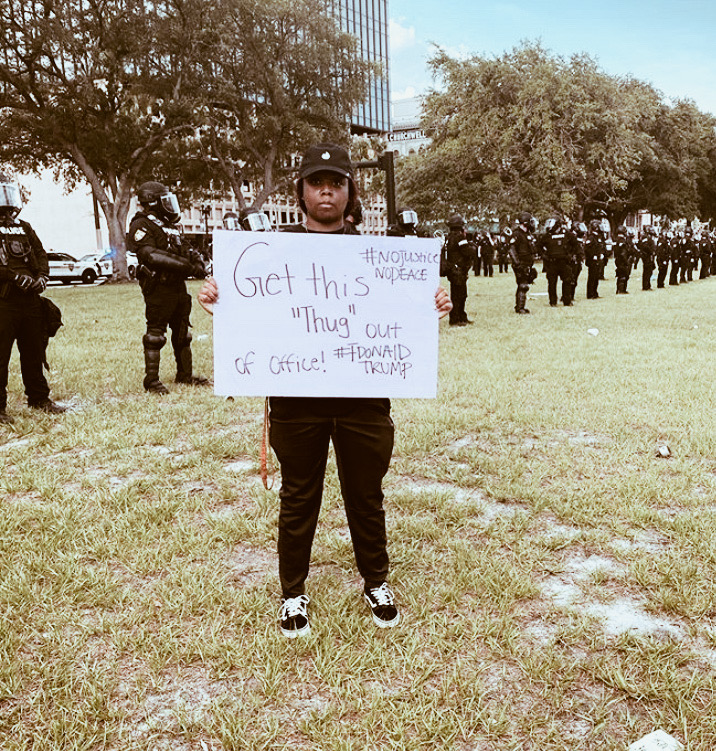

After an all call was blasted on Twitter, Hall and Carney gathered 20 people into a group chat and swiftly started plans to meet at The Capitol later that afternoon. Around 4:30 p.m. protesters gathered in the rain to join the world’s outcry for justice. Starting in humble numbers, the crowd would grow to roughly 300 people by the end of the night after news spread of the protests via Twitter and Instagram. Clenching signs emblazoned with “No Justice, No Peace” into the air, the protest gravitated from the sidewalks to the streets and solidified its message by stopping traffic.

“It’s an inconvenience to have to be fighting for the same thing that our ancestors fought for.”

“It is an inconvenience for me that I’m having to get up in 2020 and protest against racism and protest against police brutality. So, we need to inconvenience them,” Hall said. “It’s an inconvenience to have to be fighting for the same thing that our ancestors fought for, that our grandmothers fought for, and our grandfathers fought for. We are fighting for the same exact thing.”

After attending a protest organized by other impromptu leaders the following day, Hall and Carney decidedly committed themselves to the cause even if it meant traveling outside of their college town. That same day the two, along with two other friends, piled into Hall’s car and made the roughly two-hour haul to Jacksonville, Fla.

Ashleigh Hall, a senior Broadcast Journalism student, at Florida A&M University. Photo courtesy Instagram.

Ashleigh Hall, a senior Broadcast Journalism student, at Florida A&M University. Photo courtesy Instagram.

Hall, a native of Jacksonville, knew before heading to her hometown that mayhem could ensue, but not on the scale that it would swell to.

The intense relationship between the local Jacksonville community and the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office starkly contrasts police relations in Tallahassee. At the crux of tension is Jamee Johnson, an unarmed 22-year-old Black man, who was killed in a traffic stop on Dec. 14, 2020. JSO has still refused to release the critical body camera footage from the involved officers that is needed to render him justice. Johnson, who Hall revered as a brother, attended FAMU and was set to graduate from the School of Business Industry this past spring.

In cities where embattled police departments are known for militarized force or blatant brutality, protesters like Hall arrived suspicious of tensions peaking. After arriving in Jacksonville, the group joined the droves of protesters who were soon to see firsthand the escalation of violence seen in other cities online. After JSO formed around the crowd and created a deadlock, Carney said protesters grew enraged as their right to peacefully assemble was barred and subsequently, grueling scenes of police officers macing detainees in cuffs and slamming protesters to the ground began to play out.

The 19-year-old encountered the excessive use of weaponry herself when she was bombarded with six cans of tear gas while silently holding her “Justice For Jamee Johnson” sign into the air.

“I could’ve died when they threw all those tear gas cans at me.”

“I could’ve died when they threw all those tear gas cans at me. I collapsed because I was suffocating. A man ran into the tear gas and grabbed me out of the smoke. He collapsed while holding me after that,” Carney said.

In those moments when she writhed and gasped for air as the tear gas almost asphyxiated her, Carney realized that she wanted to dedicate her life to civil rights activism.

“My personal experience protesting made me want to be a civil rights activist. When you go out there, you see these people getting beat, getting pepper-sprayed, getting smoke bombs thrown at their feet and at their head. Then the police are sitting laughing about it like it’s a game. You’ll be filled with anger and sadness all at once, ” Carney said.

Her experience awakened the emotions that she had processed in the cyber world in her younger years. “I was 11 years old when I saw them kill Trayvon Martin. I was 12 years old when they let Zimmerman free. I remember Sandra Bland, which really messed with me as a kid. I remember seeing those pictures of her after she died.”

For 7 days, Carney and Hall carried those emotions from their childhood as they either led or joined 6 rallies for justice — pushing them into the forefront of Tallahassee’s rising leaders. To Tallahassee, the duo is a force to be reckoned with traveling to and fro and capturing their world of rebellion. However, with their videos going viral, both students were beleaguered by the intensified presence of media in their lives.

“I’m scared. Chynna’s scared. We’ve been getting death threats. People have been calling us stupid n-words via social media,” said Hall.

The mysterious deaths of Ferguson protesters, the conspicuous targeting of bystanders by law enforcement and pardoning of violence by the incumbent president are incidents that loomed in her peripheral as she charged the front lines.

“It’s scary. Once you put your face out there, people don’t even have to know your name. They’ll know your face,” said Hall. “I pray every night and I pray to God that he keeps me. I tell him, ‘If I die out here today, please take my soul.’”

Chynna Carney at a Tallahassee Protests. Photo courtesy Tallahassee Democrat.

Chynna Carney at a Tallahassee Protests. Photo courtesy Tallahassee Democrat.

Carney dons oversized sunglasses as a part of her protesting get-up; the sunglasses are her go-to accessory to conceal the pain of her fraught mental wellness, which is now being exacerbated by her prioritizing activism above all else. She battles clinical depression, clinical anxiety, PTSD, bipolar disorder and the trauma of a sexual assault that occurred in the midst of protests.

“A lot of people are hitting me up asking ‘When is the next protest?’ ‘Can you keep me updated?’ and they don’t even know I just need a break,” Carney said. The abrupt merging of her worlds leaves her mental health in an abyss of despair — an emotion many Black protesters know all too well.

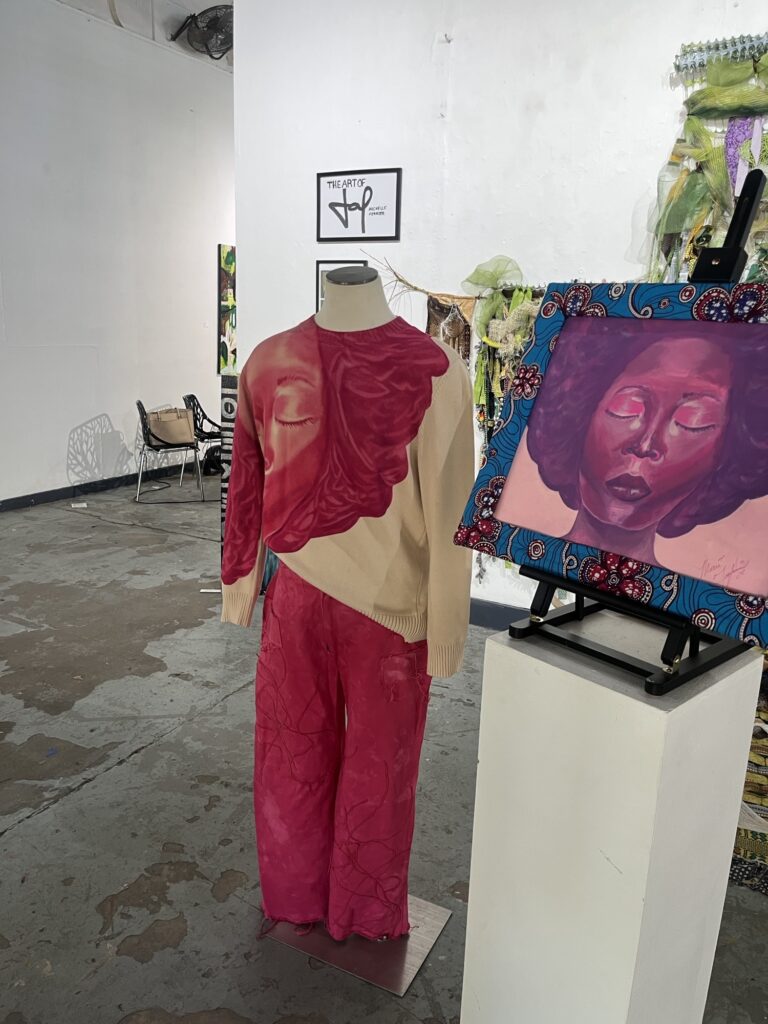

A photo series from the downtown Miami protests. Audio and photos taken by Aiyana Ishmael.

The Mental Strain of It All

By Madeline Smith

The “strong” Black friend is, likely, not feeling so “strong” right now. Along with the Black community facing alarming mortality rates from COVID-19, they are also facing the same impasse in daily life from police brutality. The nine-minute video of George Floyd’s last moments flooded social media which led to protests erupting in every state across the nation. Nonconformists of America’s recurring acts of racism are fed up and begging for a reckoning.

Many post-millennials have spearheaded protests against police brutality, nationwide, in hopes that justice will prevail for the countless Black people who have fallen victim to this sickening trend. Although the COVID-19 virus is still festering throughout many states, protesters are not as fearful of infection as they are experiencing police brutality while fighting for their [supposed] unalienable rights.

“I was nervous to go out there because I didn’t know what would happen. I didn’t know if they would try to change the narrative and make it seem like we were trying to riot when really, we are just trying to be peaceful,” Carly Griffin, a first-year, biology pre-medical student at Florida A&M University said. “In general, I just have anxiety about going into public spaces sometimes — it was a big step for me to go out and protest.”

Griffin’s anxieties turned into a reality the day she protested in Jacksonville, Fla.—her hometown. After a long day of [peaceful] protesting, Griffin sat in the grass to subside her feelings of nausea; while she was resting, Jacksonville officers began an attempt to herd the crowd of protesters. Without any warning, she was snatched up by an officer, scolded for the unknown and arrested for what was soon labeled as “unlawful assembly.”

Griffin is first from the left.

“Griffin explained that a fear that encumbered her mind throughout her encounter was being unknowingly killed in custody.”

Griffin tried to plead with the officer and explain why she was sitting, but she was ignored and shoved into the back of a blacked-out van.

“He just kept pulling me away saying, ‘You know what you were doing to get arrested,’ and the whole time I just kept saying ‘I’m sick sir,’” she said.

Griffin explained that a fear that encumbered her mind throughout her encounter was being unknowingly killed in custody. Sadly, being a Black woman at the mercy of the police, this anxiety she faced was not inconceivable.

The eerie fatality of Sandra Bland that was questionably deemed a suicide, comes to mind when thinking about the concerns of Griffin. In 2015, after the 28-year-old was arrested during a routine traffic stop after kicking Texas state trooper, officer Encinia and allegedly being combative, she was later charged with “assaulting a public servant.” Bland was threatened out of her car with a stun gun pointed at her after the officer became agitated when she rightfully disobeyed his instructions for her to extinguish her cigarette.

Three days after the incident, Bland was found hanged in her jail cell, at Waller County Jail.

“It also made me more fearful because now I see that they can do anything. They can come up with a charge and maybe lie and say that you were assaulting them,” Griffin said.

This fear has also manifested numerous times before when cops have made false allegations regarding their interactions with citizens—specifically Black ones. After murdering Black people for “resisting arrest,” “posing a threat,” or “possessing a weapon,” cops get away with these falsehoods at a disproportionate rate.

Black people are 2.5 times more likely to be gunned down by police than their white counterparts, according to figures documented on Statista.

During the earlier protests soon after the slaughtering of George Floyd, two college students in Atlanta, Messiah Young, 22, and Teniyah Pilgrim, 20, were assaulted while simply driving in their car. On a quick trip to grab a bite of food, the couple, unfortunately, got caught “out” past the assigned curfew.

The officers they encountered used excessive force in removing the couple out of the car. The two were tased and arrested.

In an interview with CNN, Young described the multitude of injuries that he suffered after the assault. He said that he had a cracked wrist, 20 stitches in his forearm, bruises on his ribs and was left with a taser jarred in his back for an extended period. He described the situation as “one of the hardest moments” he had faced in his life. Pilgrim, echoed his sentiments by expressing that she thought she might lose her life in those moments.

“Some of the force from Bloody Sunday is paralleled with the force used against protesters today.”

Although many have attended Black Lives Matter Protest nationwide, many Black people are afraid of what may happen to them should they attend.

“I have not attended a protest since George Floyd’s death—most protests are turning violent and how do I know that I won’t be the one to get shot, dragged out of my car or pepper-sprayed,” said Jordan Washington, an Atlanta native, and rising sophomore at Southern University.

Retrospectively, we have seen protests go from peaceful to violent on behalf of the cops.

Bloody Sunday occurred when some of our parents and grandparents were old enough to remember. March 7, 1965, marks the day that a slew of peaceful protesters, marching from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, were beaten with clubs, tear-gassed and whipped with rubber tubing swathed in barbed wire for “unlawful assembly,”—the same charge as Griffin.

Some of the force from Bloody Sunday is paralleled with the force used against protesters today.

Griffin explained that the protest that she attended did not begin to get violent until cops showed up—presenting force.

One may present the influx of videos depicting cops kneeling, hugging and crying with protesters, but these, arguably, performative acts cannot heal the lacerations inflicted upon the Black community by cops. Historically, law enforcement was created to systematically target Black Americans due to its derivation of policies from slave patrols.

In addition to the normal stressors that Black students face regarding school, their future careers, internships and countless other factors, they also worry about being gunned down or assaulted in the street for existing. Carrying that anxiety daily can affect anyone’s mental health extremely.

Seeing countless videos surfacing on the internet depicting the way some cops are handling peaceful protesters is disheartening for some; experiencing the force firsthand can also take a mental toll on one as well, leaving them feeling hopeless.

“We have a long fight ahead of us, and we must preserve, whatever is left of, our psychological stability.”

“We’re black, we see this go on all the time, but experiencing it first hand is just a little different. On one hand, it would be good to talk to somebody, but on the other hand, it’s still going on. It’s nothing that we can escape,” said Griffin.

After being arrested Griffin said that she experienced a “rollercoaster” of emotions. Feelings of sadness, anger and numbness engulfed her mind and she has been trying to cope.

Unfortunately, this is not a new phenomenon for Black men, women, boys and girls to be afraid of being slaughtered and assaulted in plain sight. After over 400 years, Black people are still facing the inimical outcome of being placed in a society that was created against them. These years of trauma still affect us currently.

The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) released a statement emphasizing the importance of Black Americans seeking mental health resources during this time.

It is clear that the nation, especially Black Generation Z, is fighting on the frontlines to ignite change within this country in addition to the many other diurnal challenges they encounter. It is important that we also protect our mental health. We have a long fight ahead of us, and we must preserve, whatever is left of, our psychological stability.

Navigating a Path in The New Age of Media

By Aiyana Ishmael

March of 2020 began a whirlwind of news coverage as the novel coronavirus spread across the country. Newsrooms everywhere scrambled daily to report the latest news about this ever-changing virus. The sequential deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd led to a pivot newsrooms could never see coming. Publications everywhere were watching history unfold before their eyes as worldwide protests, riots, and demand for change became headlining news. With no time between coronavirus coverage and protests, Black college journalists are learning firsthand what it means to be a Black journalist— and how intertwined their race and careers are.

Since its inception, one of journalism’s main pillars was to provide unbiased news coverage. But for many current Black college journalists, navigating their careers and their identities is leaving them at an untravelled crossroad.

“I honestly have been crying and praying a lot,” Erin Davis, a journalism student at the University of Missouri-Columbia, said. “It was a struggle for me to figure out how to use my platform as a journalist to bring awareness to everything that is happening but also tell accurate stories without my opinion slipping in.”

Police brutality and racism have always been around. Videos of Black men, women and children getting gunned down by police have been circulating on social media since Generation Z first joined. But as these young Black journalists inch closer towards their careers, this specific moment in time altogether has been more than they expected. The video of George Floyd’s death sparked an unparalleled conversation about Black lives being reduced to a supposed counterfeit 20 dollar bill.

“As a Black journalist still in academia it has been a bit tough to navigate as I have fears of being blackballed or losing scholarships from USC,” Daric Cottingham, a Masters student at the University of Southern California said. “But that fear is outweighed by my obligation to speak out. The idea of objectivity is not a luxury Black journalists get to have. It breaks my heart to know there’s a cycle of systemic racism at every level and the fear of losing your job for speaking out.”

“I cannot sit idle while my people are dying. I have had enough of the brutal, inhumane, and unjust killings of black people.” – Justus Hawkins, Morgan State University

The industry is already tough to break into in general. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics overall employment of reporters, correspondents, and broadcast news analysts is projected to decline 10 percent from 2018 to 2028. Now factor in being an entry-level Black journalist trying to be hired in the coming months. According to data from the 2018 Newsroom Diversity survey from the American Society of News Editors, Black journalists make up only 7.19% of newsrooms.

Media was hit hard amidst COVID-19 due to budget cuts, leading to layoffs and furloughs of hundreds of journalists in newsrooms across the country. This leaves emerging journalists in an extremely competitive job market.

Twitter and Instagram are where many working industry professionals have voiced their disdain for the current climate in America. But there have been several Black journalists who have been barred from covering current events because of their personal views. White leaders in varying newsrooms play a fundamental role in how upcoming Black journalists carry themselves on social media. The current battle many young Black students face is finding a healthy balance of information to share.

“I’ve shared some things I agree with, but I’m hesitant to get too personal because I feel like I need more time to process. We’re taught that as journalists we’re constantly scrutinized,” Daja Henry, Masters student at Arizona State University’s Conkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, said. “I don’t think this [moment] has shown me anything I didn’t already know. Racism has been repackaged time and time again. However, it’s sad to know that there are people who view historical facts as opinions or fake news.”

“This is a pain that’s accumulated for so long, that [Black people] are willing to risk their lives during a pandemic to bring light to the fact that they feel unsafe in their interactions with law enforcement.” – Sophie Austin, American University

Student publications are playing a huge role in the hyper-local coverage of their respective towns. And while these newsrooms are taking this moment in time to produce full-coverage, Black students are battling emotional turmoil watching their people lose and fight for their life.

“I think the hardest thing I’ve learned during this is that while it’s important to cover stories, I’m also a human being and that I’m allowed to feel sad, process, and, or stand in solidarity,” North Carolina A&T State University student, Lauren Mitchell, said. “My wellness matters.”

News consumption has reached an all-time high for many young journalists as COVID-19 cases and protests continue to run rampant. Many students are realizing that time away from social media and the news will play an important role in their mental health.

“The more young journalists like me cover the information— no matter what number of followers we have– the more people can be informed,” Ayana Evans, Hampton University

“I’ve been keeping up with the national news and analyzing media coverage with a more critical lens,” Norah Mulinda, a fourth-year media studies major at the University of Virginia, said. “I have found it extremely necessary to take a break from consuming news all day long because it can be very depressing and have a drastic effect on your mood and subsequently your entire day.”

Simultaneously, as protesters took to the streets to protest racial inequities, Black journalists were stepping forward to discuss the discrimination and verbal aggression they’d received from their white colleagues. The hashtag, #BlackatR29, went viral as several Black women and women of color came forward to voice their concerns with the blatant disregard for Black women and their ideas.

On the heels of this movement, several other Black women stepped forward from newsrooms all over to speak on the emotional and professional exclusion they received. This unloaded an important conversation around the need for Black ideas, but not the support of the women holding them. For many aspiring Black journalists witnessing the ostracization of the Black women they admired felt personal.

“Do I enter the field I’ve dreamt of for years and risk experiencing racism at multiple levels? Do I forfeit my dreams to protect my inner peace? Do I strive toward media in hopes of entering spaces and breaking barriers for my Black peers? I don’t currently have the answers to these questions but they have been weighing heavily on me,” Aniyah Morinia, a spring 2020 graduate of the University of Florida, said. “I want nothing more than to feel safe and valued in my career, but Black women in media are feeling the complete opposite and it’s heartbreaking.”

And while there are so many complex feelings running through young Black students’ heads, there’s one thing they remain sure of— the need for Black journalists. A diverse newsroom leads to accurate news coverage. Especially right now Black people must tell their stories. Black journalists are needed in all areas of the newsroom.

“I’ve felt more inspired by this because it reminds me why I chose this field of study in the first place,” Brittany Jarret, a broadcast journalism student at Florida A&M University, said. “I will help get people’s stories heard, especially the ones that tend to slip under the rug.”

#SayHerName Cannot be Co-opted Just Yet

By Aiyana Ishmael & Mia Uzzell

Shortly after the clock struck midnight in Louisville, Ky., three plainclothes LMPD officers arrived at the home of Breonna Taylor to execute a search warrant, with a distinct no-knock provision, for an ongoing narcotics investigation.

Taylor, an emergency paramedic technician, hastily awoke from her sleep when sounds of entry echoed through her apartment, and her boyfriend Kenneth Walker grabbed his firearm in defense. In Walker’s recollection, Taylor alarmingly pleaded “Who is it?” “at the tops of her lungs.” After no verbal response from who they believed to be intruders, the licensed gun carrier first fired shots when the front door “came off its hinges.”

Moments later, the officers released a barrage of gunfire into the home. Over the phone, Breonna Taylor’s mother would soon hear Walker shout with anguish “I think they shot Breonna.” In the wee hours of that March 13 morning, at least eight bullets struck the 26-year-old and she was pronounced dead on the scene. Roughly two months shy of her 27th birthday, the aspiring nurse left behind a poignant legacy of love, light and service.

Her story rose to prominence after languishing in media coverage that originally cast her as a suspect. And even in its early glory days, the gravity and breadth of her story were minimized as the footage of Ahmaud Arbery’s killing on Feb. 23 gained traction.

On his route through a neighborhood outside of Brunswick, Ga., the 25-year-old avid jogger was suspected of burglarizing houses and was pursued by Travis and Gregory McMichael. In an attempted citizens’ arrests by the father and son, Arbery was fatally shot in what many on social media interpreted as an irrefutable case of racial profiling.

“I’ve seen a lot of media outlets and singular activists remove Breonna Taylor’s name and her story from the forefront.”

Over a month apart and over 700 miles away, Arbery and Taylor, only separated by a year in age, lost their lives during the mundane activities of life: sleeping and going for a run.

When hashtags for Ahmaud Arbery submerged timelines, in the middle was a power struggle with Taylor’s story for virality. Many Black women used their digital forums to prompt an arousing dialogue as to why Taylor’s story didn’t simultaneously receive the recognition it deserved. The upshot from the discussion was that the boundless litany of Black women who have been slain by violence isn’t even enough to impel the nation to seek justice for Breonna Taylor, too.

Kiana Stevenson is the curator of Listen To Black Women, a digital community for Black women that touts a “for us, by us” platform motto. The 19-year-old media savant expressed how disconcerting it was to scarcely see the same activism awakened for Taylor.

“I have seen a very questionable erasure of Breonna Taylor. I’ve seen a lot of media outlets and singular activists remove Breonna Taylor’s name and her story from the forefront,” Stevenson said.

The “questionable erasure” Stevenson mentioned was a daunting portent of what was soon to be birthed after the death of George Floyd. When Minneapolis was engulfed in flames following Floyd’s death, protests in his namesake jolted the nation to shoulder its history of condoning brute force against Black people. The epicenter of this national reckoning was George Floyd, but in a domino effect, people hit the pavements nationwide to air out their long-overdue grievances.

In Jacksonville, Fla., Stevenson attended the “I Can’t Breathe” Solidarity Reflection Walk. The titular phrase were the words heard in the bystander video of Floyd’s death as Officer Derek Chauvin kneeled onto Floyd’s neck for nearly nine minutes. Those same three words once echoed across the nation six years ago in the killing of Eric Garner by NYPD officer Daniel Pantaleo.

“Who is Breonna Taylor?”

During the walk, organizers led the call and response chant “Say His Name, George Floyd” with their megaphones. Stevenson parted through the crowd to ask them to similarly amplify Breonna Taylor in the same rallying cry. To her dismay, they responded “Who?” completely oblivious to the existence of Taylor’s heart-rending case.

The harrowing response lingered in the back of her mind. Contemplatively processing what she just heard, Stevenson thought to herself: “[Breonna’s] story was just circulating days before him, hours before him.” Those three mere letters were emblematic of the brevity of acknowledgment Black women receive in the very movement that they created. #BlackLivesMatter was a hashtag Black women introduced and yet somehow, Black women are still exiled in the fight they proudly walk on the frontlines of.

“Our movement is spearheaded by Black women but the conversation is going to be about cis-gendered black men,” Stevenson said. “It is sad to know that even if I were to die tomorrow, it would not be taken as seriously because I am not a black man.”

Say Her Name: a phrase coined during the Black Lives Matter movement to bring Black women back into the main discussion. The stories of Black women are far too often discarded into a chasm of obscurity.

“It is up to us to amplify Black women because if we don’t do it, no one will do it. It takes one person to say her name for someone else to research her story and then ignite someone else to be outraged to fight for justice as well,” Stevenson said. “Black women turning to their timelines to call out the erasure of their stories is “just another example of the fact that Black women ride the hardest for Black women, Black women do the most for other Black women, and Black women protect Black women.”

Black women are extremely vocal during the fight for all Black lives, but it became apparent recently that for many Black men their support of Black women was conditional.

It does not take ownership of a Black woman to value her life. It does not take sexual attraction to value Black women. But, it is also important to note that Black women deserve to be supported and uplifted before they are six feet in the ground.

On one hand, it is cathartic to see the dismantling of the system in real-time, but on the backend, the activism that rises like a phoenix for cis-gendered black men leaves the sweltering ashes behind for black women and especially trans women. The #SayHerName movement must be intersectional to truly make progressive strides. If it doesn’t fight for all women, then the movement essentially fights for no women.

Even more beyond the push for equality, there must be a movement towards protecting Black women from sexual assault. According to the National Center on Violence Against Women in the Black community 1 in 4 Black girls will be sexually abused before the age of 18. The data goes on to say that African American girls and women 12 years and older experienced higher rates of rape and sexual assault than white, Asian, and Latina girls and women from 2005-2010.

Anyways I was molested in Tallahassee, Florida by a black man this morning at 5:30 on Richview and Park Ave. The man offered to give me a ride to find someplace to sleep and recollect my belongings from a church I refuged to a couple days back to escape unjust living conditions.

— Oluwatoyin (@virgingrltoyin) June 6, 2020

Oluwatoyin Salau was a 19-year-old Black woman and Tallahassee native. Salau was extremely vocal in the past few weeks about the mistreatment of Black people. In an interview during a Tallahassee protest, she goes on to say how vital it is to fight for all Black lives, including Tony Mcdade, a transgender man that was fatally shot by the Tallahassee Police Department.

Oluwatoyin “Toyin” Salau

Rest in Power Angel 💔 #JusticeForToyin after tweeting about her sexual assault she went missing for several days and her body was recently found. She was only 19. pic.twitter.com/4uAlVsAVHK— Shari ✨ (@shariauna_) June 15, 2020

“It’s not that all lives don’t matter, but right now our lives matter. Black lives matter, Black trans lives matter.” Salau states. “We’re doing this for our brothers and sisters who got shot. We’re also doing this for every Black person because at the end of the day I cannot take my skin color off.”

On June 6, 2020, Oluwatoyin Salau went missing. This was a few hours after she’d attended a protest, lost her phone, and released a thread on Twitter explaining how she’d been assaulted. For a week Oluwatoyin Salau was missing. Students of the Tallahassee community took to social media urging TPD to help find Salau. On June 14, 2020, Salau was confirmed dead by TPD.

Within hours of finding out of her passing, Oluwatoyin Salau’s name went viral. Overnight the world would know of Salau’s story making up over 500,000 tweets about saying her name, calling for justice, and mourning for the loss of such a young life.

Friends and strangers-alike noted that while they will gladly shout “Oluwatoyin” from the rooftops, there needs to be more regard for Black women before their life is cut short.

Protesters in Tallahassee, Fla., walking and driving the streets in honor of Oluwatoyin Salau. Photo taken by Aiyana Ishmael

Protesters in Tallahassee, Fla., walking and driving the streets in honor of Oluwatoyin Salau. Photo taken by Aiyana Ishmael

What Comes Next?

2020 became the year where young Black adults stepped into the forefront of the fight. There are several roles needed to be filled during this moment in time. The empath, storyteller, and protester are all valiant roles during this prolonged push for equity.

Young people across the country are in the streets leading protests, raising money for bail funds, and telling important stories, all while focusing on their well-being. Generation Z is utilizing their history to fight for the future they want. To be young and Black in America is to be tired and willfully ready for change.

“I hope this moment is one of many true steps toward Black liberation that we will see in our lifetime,” Grey Stricker, 21, said. “I hope this moment leads to the defunding of police, and it’s inevitable abolition. Not only of the police but of prisons and the prison industrial complex. I hope this spurs even further to the demolition of our current capitalist state. I hope community and humanity are valued above all else.”